By Kelly Patrick Slone

“When ‘progress’ calls for redevelopment of cities, African-American sites and structures are often the first to disappear. In small towns and rural areas, Black landmarks frequently fade into obscurity.” — Indiana Landmarks.

Indiana Landmarks, a private statewide historic preservation group, doesn’t necessarily fight progress. Rather, it works to ensure the developments of today and tomorrow maintain respect for yesterday’s structures and the value of Hoosier history.

“Each building represents a different goal and achievement that a community has. For that reason, we’ve always felt whatever kind of structure it is, it played an important part in our history,” said Mark Dollase, Indiana Landmarks vice president.

But a couple decades ago, Dollase said the organization realized their focus needed to be broadened.

“For so long, the arc of the work that we do had been focused on the most important works of architecture in our state, and when I say ‘most important,’ I mean specifically in the design of the structures or who built them,” Dollase said.

“And most often, those were wealthy people who back in the 1800s, early 1900s had the financial means to build places like that. And most often those were wealthy white people, to be blunt.”

In the early 1990s, Indiana Landmarks decided to reevaluate its focus to include more diverse initiatives, which led to the creation of a group that’s been key to saving and restoring significant African-American sites and buildings across the state.

“Indiana Landmarks set up the African-American Landmarks Committee (AALC) at that time, and we began by doing some studies of key buildings that we thought needed to be preserved that had a support system around them. And that led to some significant restoration and rehabilitation projects,” Dollase said.

With help from the Indiana Historical Society and the Indiana Historical Bureau, the AALC conducted a survey and identified 330 buildings and historic sites across the state that are important to African-American history.

After identifying their targets, the AALC could really get down to business. When asked for some of the highlights of the committee’s work, Dollase mentioned significant “saves” in Jefferson County, Marion County and Vigo County. Dollase said he oversees eight regional offices across the state, which helps to keep tabs on projects and work with communities in their respective regions.

One project in particular that Dollase said Indiana Landmarks was especially pleased with was the restoration of St. Stephen’s AME Church in Jefferson County, just outside Hanover, Indiana. The church, which was built in 1904, was in bad shape.

“The building not only was run down, but the congregation had dwindled down to about 10 people,” Dollase said.

Indiana Landmarks was able to revitalize the building, which helped the church attract new members and led to a turnaround in the congregation itself. Dollase said it was a prime example of Indiana Landmarks ability to use a “building and its heritage as a source of energy to help inspire people.”

Another significant church project that had major help from the community was the restoration of Allen Chapel AME in Terre Haute.

“Some us in the community formed a group called the Friends of Historic Allen Chapel, and that group has raised since the mid 1990s about $600,000 that’s been put into the building,” Dollase said.

The church now has a new roof, updated wiring, revamped heating and cooling, and remodeled restrooms and kitchen. The building was also updated for accessibility and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The biggest expense — to the tune of about $125,000 — was restoring all the church’s original stained glass windows.

Dollase said Indiana Landmarks has made definite progress preserving the state’s African-American sites since the AALC was formed, but there are still constant threats and challenges.

“We are constantly having to educate the development community as to why these places are unique and special. We’ve fought off several threats over the past few years in Indianapolis,” he said.

Dollase said the group just hopes for a better understanding that certain sites are “off the table” for demolition, though as a compromise, some can be “incorporated into someone’s project, so that piece of history is still there to tell the story of both the African-American community and the city of Indianapolis.”

“I think there are unique and different ways we can make sure these special places continue to be a part of our lives going forward,” he said.

And just because Indiana Landmarks has touched a community, doesn’t mean the challenges stop.

“One of the properties that we spent an extensive amount of time and money on saving was the Second Christian Church, which is in the middle of the Ransom Place Historic District (in Indianapolis). That was really the eyesore of the neighborhood, and we knew if we could fix that building and bring it back, it would help revitalize other buildings in the neighborhood.”

But that revitalization has caught the eye of developers, who have big plans for “improving” Ransom Place. Dollase said many plans have been proposed for large developments that are out of scale for the quaint, homey neighborhood, and while many have been shutdown, Indiana Landmarks’ work is never done.

Tour Indiana’s African-American landmarks

Mark Dollase, vice president of Indiana Landmarks, a private statewide historic preservation group, listed some of his “must-see” African-American heritage sites around Indiana.

Roberts Settlement (Hamilton County)

Free Blacks who migrated mostly from North Carolina and Virginia founded this African-American pioneer farm settlement in 1835. A chapel and a cemetery are today’s reminders of the thriving community that once called Roberts Settlement home.

Georgetown District (Jefferson County)

This neighborhood, along the Ohio River, housed free Blacks as early as the 1830s and included at least eight sites on the Underground Railroad. More than 70 percent of the neighborhood’s original structures still stand, including two churches that were Underground Railroad stops and the homes of several Underground Railroad leaders.

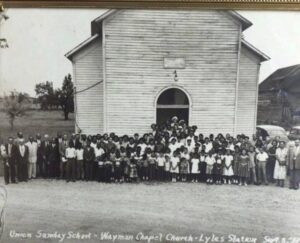

Lyles Station was settled in the early 1800s and is one of the last remaining African-American settlements in the state. The Lyles Station School has been preserved and renovated, and the Lyles Station Museum was created. Several events and programs are put on at Lyles Station, including a program for school fieldtrips.

Civil Rights Museum (St. Joseph County)

A civil rights museum has been set up at a natatorium building where the pool was whites-only six days of the week. Dollase said once a week, the pool was completely drained and refilled, so the Black community could swim. After that day, the pool was again drained and refilled for the whites-only days.